What is reality? Are we real? By exploring the work of philosophers and analysing ourselves, let’s look at what we can call real and how our perception of reality might shape our lives. What happens when we stretch our thinking to the limit of what’s real?

Are you real?

To some it might seem like a stupid question: Are you real? Of course I’m real! If I weren’t real, I couldn’t be reading this article right now! Nevertheless, reading is a complex biological process: you perceive the letters with your eyes, and your brain constructs ideas from the words you see.

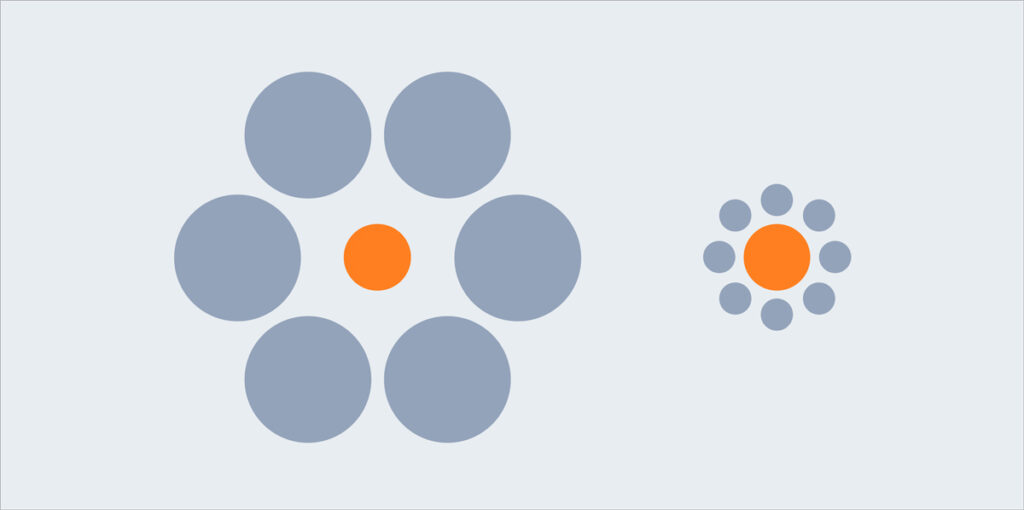

The dot at the right seems larger than the dot at the left, yet they are both the same size. (measure with a ruler)

As a result, you understand what is written, because reading is a process of the brain that is not reliable. In fact, you can’t rely on any of your senses because they are easily tricked.

So why should your thinking be any different? Sometimes people make logical errors which we call paralogism. Take, for example, this picture of two orange dots. The dots seem to be of different sizes, yet if you measure them with a ruler, you see that they have both the same radius. This is called an optical illusion. There are many different kinds of illusions which rely on different senses or perceptions.

Plato’s allegory and the beginning of the philosophical debate

To start our analysis, let’s look at one famous allegory of Plato. Plato was a philosopher who lived in the 4th and the middle of the 3rd century B.C. In his allegory, a person is chained up in a cave since birth and is forced to look at a wall for his entire life. At the entrance of the cave, there is a fire which illuminates the wall and makes it possible for him to see the shadows of objects as they pass in front of the fire. So, he gets presented with different objects like a fork, a chair, a vase, etc. The prisoner learned to recognise these objects and for him the objects are the shadows he sees. They are his reality. For the purpose of the discussion, let’s suppose the prisoner is freed when he reaches adulthood, and he can go outside the cave. Would he be able to recognise the objects? No, he would not, because he is not used to seeing the world in three dimensions.

This allegory contributes to a paradigm shift where philosophers stop seeing reality as a general and universal truth, but rather as a particular and personal representation of the world within an individual’s mind.

Among other famous examples, there is the argument of Emmanuel Kant, a German philosopher who lived in the 18th century. He based his ideas on the theme of epistemology, the study of the human limit to knowledge, inspired by the question what can we know? Kant concluded that our knowledge is limited by our senses and our physical body. This means we can’t perceive every aspect of our physical world. That’s a logical conclusion considering there is a lot of information from our environment like UV radiation, atoms or magnetism, we can’t detect. Our reality is limited by our senses.

These limitations can be explained through the principle of evolution. Put simply, we can say that we don’t need to perceive much more of the world than we do now because it doesn’t give us much of an advantage concerning our survival and reproduction.

What is reality ? What is truth ?

So far, we have learned that reality is in fact our subjective perception of our environment. For the sake of the argumentation that follows, let’s define reality as the world outside our mind, which we only partially perceive through our senses. In Kant’s terms, reality is the “Ding an sich” (“the thing itself”). Our perception of reality which is a construct of our brain reacting to stimuli from the environment (extern) or from within (intern). Let’s call the smallest unit of a stimulus “information”. By rephrasing Kant’s ideas, we can say that a stimulus is the sum of information. We can respond to a stimulus automatically, but we have to break it down manually (by thinking) in order to get the information it contains.

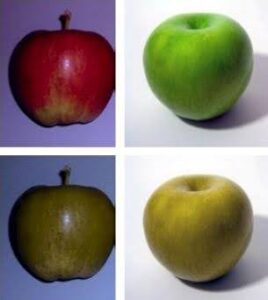

Normal view on top Red-green colour-blindness view below

Let’s take the example of a red apple. You can tell that it’s an apple because you learned to recognise it. The image of the red apple is like a stimulus. Extracting information is like asking specific questions: What colour is it? (red) How heavy is it? (about 150g) What’s the aspect of the apple? (smooth). If you asked many people, you would realise that their answers aren’t all the same. But why? The reason is that the nature of the stimulus is different. Even if, in reality, the red apple is the same for everyone, the people’s perception can vary. Because we descend from a common ancestor, we belong to the same species. We are all humans. So the biological structure of our senses is very similar, but not identical. Even though the structure of the eye is very similar, a person with red-green colour blindness sees a brown apple and a normal person sees a red apple.

We conclude that changing an information (the colour of the apple) doesn’t change the nature of the stimulus (the apple doesn’t become a pear), but changing an information alters our perception of the stimulus (the red apple becomes a brown apple).

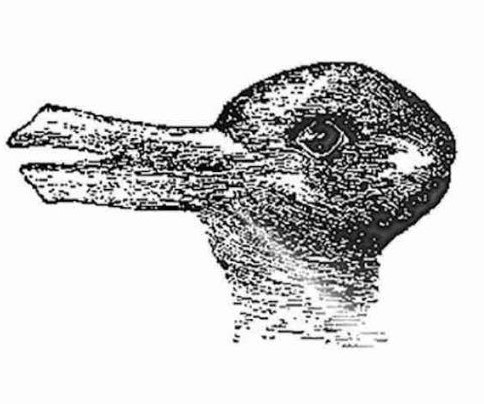

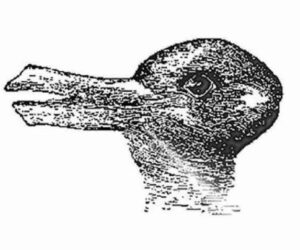

Is it a rabbit or a duck ? Or do you see something else?

Another aspect of subjective perception is the mechanism with which we interpret stimuli. We don’t all think the same way. Our brains are fundamentally similar because we are similar, but individually everyone has a different brain. Among other factors, genetics and experience are most likely to shape our brain. Our personal experiences differ from culture to culture, from place to place, from one environment to another. Our environment is everything in the physical world which can induce a change in ourselves. Familial, cultural, academic or social context shapes our mind. We are made from our experiences.

Because our brains work differently, and we think differently, it is inevitable that we have different opinions on the same matter.

For example, some people see a duck in this image, others see a rabbit. Both parties are right. How can it be a duck and a rabbit at the same time?

As we have seen, the world is not absolute. We create an idea of the world by perception, and perception is subjective and even relative (we don’t explain it in this article). Our environment doesn’t bother giving us a clear stimulus, because reality can never be summed up by perception. We have to accept that both parties can be right, or that both parties can be wrong. Why should one party be right over the other? In some way we can say that the truth itself isn’t absolute (duck or rabbit or both or none). But if the truth isn’t absolute, is it still a truth? Yes, the truth is the point of view of most people. So, if the majority shifts, so does the truth. Remember when the Earth was flat, it was the truth at that time. Today the Earth isn’t flat, but a sphere. (To be correct, Earth isn’t a perfect sphere. It’s flattened at the poles.)

How to live with uncertainty?

We live in a physical world where everyone creates their own view of their environment through perception which is both uncertain and subjective. Conflict arises where different views collide, but I hope I gave you a glimpse of a thinking process which questions reality. Don’t feel insecure because you doubt. Doubting is a necessary process which creates humility. Those who don’t doubt are most likely to err. If you know your limits and recognise the limits of others, you’ll start to see things you didn’t realise before. After all, you are just reading a silly article in a paper. It is up to you to choose how it changes you.