Nightline: Available via Phone, Chat & Mail

During its early years, Nightline Zurich was only reachable by phone and saw a moderate number of calls. However, with the introduction of the chat system in 2017, the service experienced a huge increase in contacts. It seemed like the possibility of chatting instead of talking made conversations with strangers less scary and more accessible. Furthermore, despite being more impersonal than phone calls, the relief these conversations provided was apparently still sufficient. Thus, considering the improvement of conversational AI over the past few years and the increased demand for mental health support, the question poses itself, whether a well-adjusted chatbot could replace a human partner in these chat conversations and still deliver similar support.

Eliza

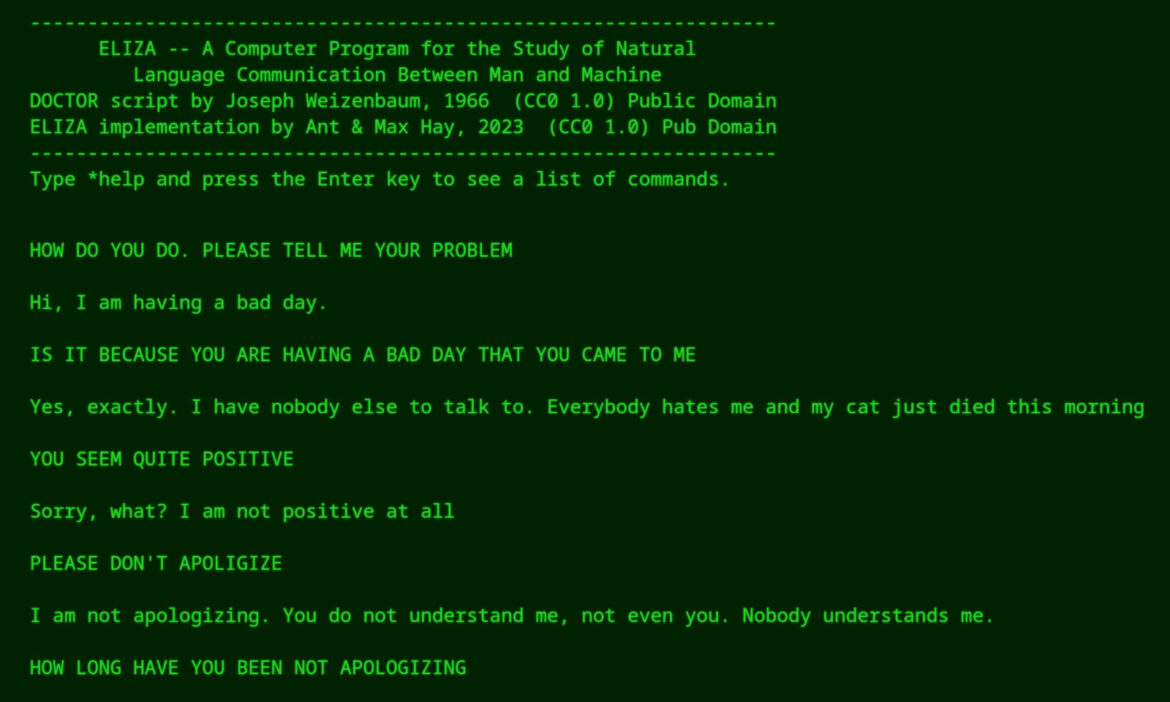

The idea of using chatbots to replace humans as conversational partners is older than one might expect. Already in the mid-1960s, Joseph Weizenbaum developed Eliza, a program that was able to communicate with humans via text messages using a simple rule-based approach to natural language processing. It would analyze the given written inputs by looking for keywords in the text, which were then used to craft a response according to a rule set predefined by the developer. One of these rule sets was the Doctor script, whose goal was to imitate the responses of a therapist. This relatively simple concept already showed impressive conversational capabilities and many people at that time felt like they were talking to an actual therapist.

While Eliza was originally developed to explore the natural language processing possibilities of computers, a growing number of services today try to provide serious AI-based support for mental-health-related topics. By using large-language models, these new chatbots allow for longer and more coherent conversations and often provide reasonable and helpful responses, that feel more human than those of rule-based Eliza. The aim of these services is to satisfy the growing demand for broadly accessible mental health care and make therapy accessible for those who cannot – or do not want to – go to real therapy.

The Good vs. the Bad

These systems may have some advantages over traditional therapies, like reduced costs or availability at any point in time whenever the patient faces a mental health crisis. Additionally, some patients may feel more comfortable talking openly to chatbots since there is no possibility for judgement or stigma, when there is no real person involved in the conversation. However, there are rising concerns about this kind of therapeutic approach. Research has shown that patients talking to chatbots were aware of the fact, that there was no real understanding of their problems on the computer side and quickly lost interest in the conversation after getting some responses that did not correspond to their expectations or wishes (Buis, An Overview of Chatbot-Based Mobile Health Apps, JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023). This lower acceptance of unwanted responses may be especially critical if the life of the patient is at stake. In the case of suicidality of the patient – even if the system would be able to correctly identify and react to the situation – its response may carry less weight for the patient than if it were provided by a human being. Tailoring the responses of the chatbot to cater to the patient’s expectations can be equally problematic. Such a chatbot would not only amplify a possibly unhealthy worldview, but it would also give the user total control over the relationship between the “therapist” and themselves. This may lead to an unhealthy attachment of the patient to the bot and lower the user’s tolerance for real human relationships, which are shaped by disagreements and reconciliations, misunderstandings and clarifications. These increased expectations in their conversation partners could hinder the patient’s ability to make connections with ordinary people, further isolating the users from the people around them.

Some Uncertainties Remain

It has been shown that the most significant indicator for the success of a therapy – or any other interhuman interaction – is the relationship between the people taking part in it (Flückiger et al. in Counseling Psychology 2012). While well-trained algorithms allow chatbots to mimic empathy and understanding on a level that can often lead to a strong humanization of and bonding to the system, it is still unclear how this compares to a therapeutic relationship between real human beings. After all, treating a chatbot as a human involves some kind of (self-)deception about the nature of the conversation partner, and even the most valuable contents of a chatbot’s responses do not change the fact that we are still alone with our lives. Therefore, with chatbots possibly becoming a valuable part of our mental health toolbox, like keeping a diary or going for a walk, they will not replace human interaction as an integral part of our wellbeing.

The goal of Nightline Zurich is thus to provide the possibility for a human connection between students in an anonymous and easily accessible fashion. Writing in the chat there, you will always talk to a fellow student who listens and understands such that you are not alone. Therefore, if you need someone to share something, be it happy or sad, if you need someone to talk to or just be there for you, write to Nightline or maybe even take the phone. We listen to you.

Gabriel Margiani, 29, doctoral candidate in physics. As president of Nightline Zurich, I often think about what constitutes an effective empathetic conversation and what to do about the loneliness of students.