by Riccardo Giacomello

”No more than 30 minutes“, my mother used to say when she allowed me to dedicate my childly energy to the vibrant world of the Nintendo GameCube. Around the age of ten, the Mario franchise, with its kart racing and football games, was one of my brother’s and my dearest leisure activities, and our parents viewed it as their responsibility to control our time spent on this hobby. Luckily, they didn’t notice when those 30 minutes grew into 35 or even 40. Still, their regime was rather strict, and they sought to limit our access to games in different ways. In all the time from our first old GameBoy Color to the later strategy games (does anyone still remember Age of Empires?) there was a constant tug-of-war between kids and parents: passwords, cracked passwords, Gameboys hidden in the closet, Gameboys detected in the closet and so on. And of course, gaming time was in a continuous negotiation. The slight but steady shift to more time reflected the increase in our bargaining power as we grew up.

Then, at some point, the game was over. I don’t even remember if the stop was conscious or unconscious, gradual or sudden. Was it because the school, the first small income-generating activities and the start of university demanded more and more time, and videogames began to seem like a waste of an increasingly scarce resource? Was it because this childish hobby didn’t fit with the desire to grow up? Was it because the interest in games correlated negatively with the interest in the fairer sex?

The Rise of Video Games

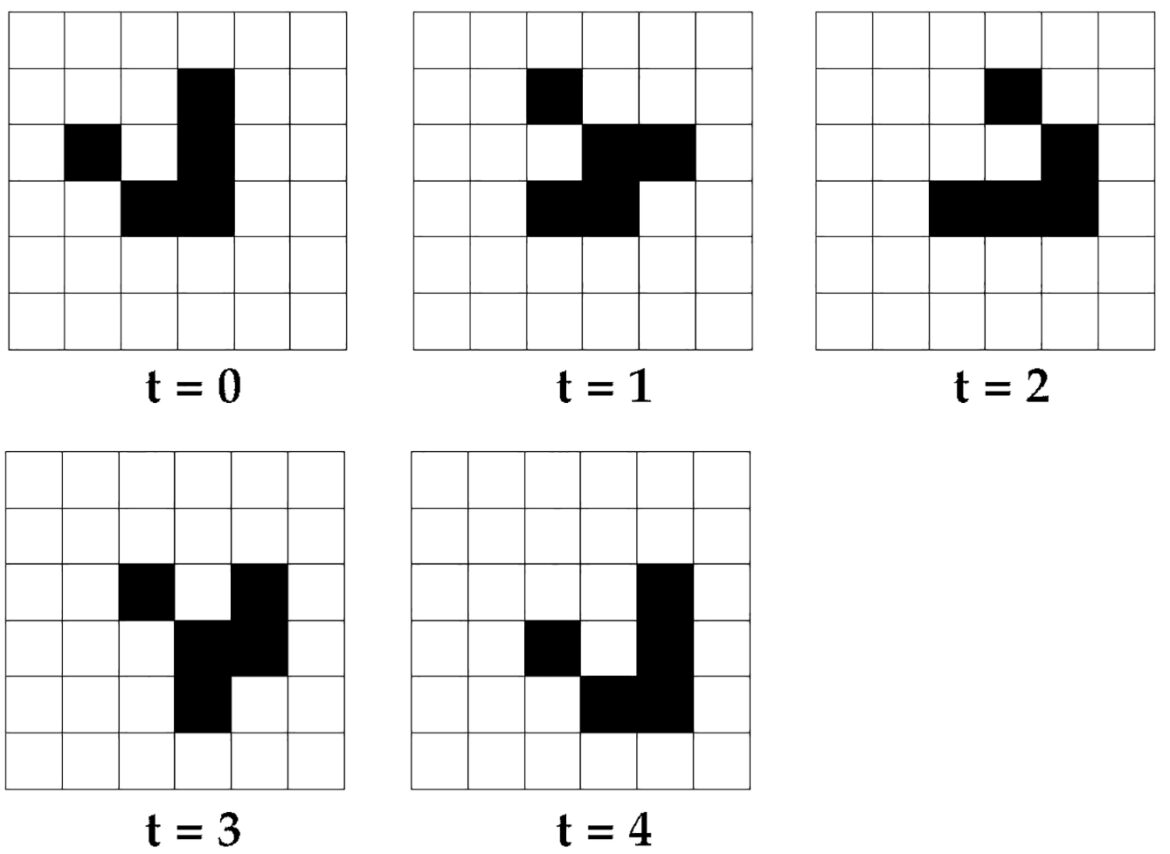

Since then, video games have been largely absent from my life; but now I regard them more highly than I used to. Since they first appeared, games have experienced an incredible evolution from primitive to highly complex, literally mirroring the development of life on Earth. What originated in the fifties as a mere gadgetry of scientists at US universities became a commercially successful mass phenomenon for the first time in 1972 with the famous Pong. Soon thereafter, exchangeable cartridges, home computers, more complex game play, and a skyrocketing computational and graphic performance turned video games into one of the most dynamic industries worldwide. Fuelled by the pandemic, the volume of sales now exceeds 150 billion dollars a year, far more than the film industry. A third of the world’s population plays video games, and their hobby is more and more being recognised as a sport.

Virtual vs. Reality

As they become ever more realistic, the distinction between games and reality begins to blur. A development that started with games simulating reality, like the Sims or Minecraft, and resulted in today’s complex immersive VR experiences may take us much further: Why should we not collect our ECTS, earn our money and make friends in a virtual world? And while this may not sound very appealing, what if all wars were fought in a virtual world? From here the speculations have no limit. Isn’t life itself akin to a video game? We walk around, collect coins, and try to “level up”; we just don’t have a save and load button. Life, as certain philosophers have suggested, might even be indistinguishable from a simulation.

What happened to our old GameCube? Recently, we dug it out, my brother and I, when we visited our parents. It must have been in the basement for over a decade. But it’s still a lot of fun.

Riccardo Giacomello, 26, studies Comparative and International Studies. If this wasn’t so time-consuming, he would probably try to get better at Mario Kart.