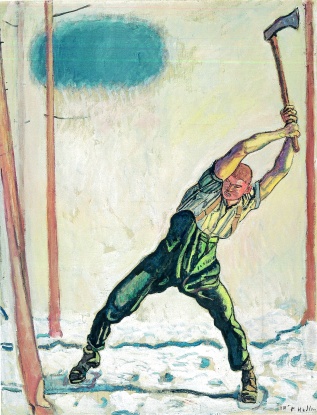

A powerful man chops down the last trees in a bleak landscape: Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler’s famous “Woodcutter“ opens up the temporary exhibition “In the Forest. A Cultural History“ at the Swiss National Museum. The painting from 1910 is nowadays more relevant than ever. Man dominates nature; he overmasters it, but this power ultimately threatens himself. When all trees are cut, he will be all alone.

An inseparable whole

The division between culture and nature runs through our history since we left the “state of nature” through the neolithic revolution. The first forest clearances in that epoch marked the beginn- ing of a steadily growing use of forest resources that culminated in the large-scale destruction since the industrial age. This history constitutes the first main part of the exhibition. It turns out that the division between culture and nature is misleading: humans continue to be totally dependent on and a part of nature. The woods are our original home; visiting them boosts our health, strengthens the immune system and lowers blood pressure. And the fact that humans are lost without nature surrounding them was realised in Switzerland in the 19th century, when the deforestation of mountainsides for industrial purposes came at the cost of devastating landslides.

From destruction to restoration

The view of the forest as a human habitat and as an ally instead of a simple resource for exploitation points to another focus of the exhi- bition: the protection of the woods. Here ETH had an important role, having trained forest preserva- tion specialists as early as its foundation in 1855. Moreover, progressive legislation acknowledged the importance of trees as protectors from land- slides and avalanches. All this led to a recovery of Swiss woods over the past 150 years. The problem of deforestation has shifted since then to tropical areas, where numerous indigenous peoples call the forest their home. How their fight against rainforest destruction was also supported by Swiss people like Bruno Manser is explained in the exhibition as well.

What lies ahead?

A third topic is the presentation of forests in art and literature. It is shown how they inspired philosophers, romantic poets, fairy-tale authors and modern filmmakers. Paintings are often idealising; the more modernity has torn man from his primordial bond with nature, the more nostalgia and romanticisation of wild, pristine landscapes. The problem of deforestation ultimately called performance artists to action. Klaus Littmann planted 299 trees in a stadium, implying a future in which nature can only be seen in narrowly delimited reserves.

The story at the museum ends with this grim outlook, with little hope for a positive turn: a sculpture of a dead olive tree. But as necessary as change is, it is also still possible. Unfortunately, the exhibition doesn’t discuss what can be done. Which political and economic measures could stop deforestation? How much would the promotion of plant-based nutrition contribute? Are environ- mental protection and material prosperity re- concilable? Such and more uncertainties persist as we leave this beautiful but worrying exhibition.

The exhibition “In the Forest. A Cultural History” is open until 17 July 2022.

Riccardo Giacomello, 26,

studies Comparative and International Studies. He agrees with Jean-Jacques Rousseau that forests are among the best places to find happiness.